For a long time, consent was treated like a speed breaker.

Something users clicked past.

Something companies buried at the bottom of a page.

Something that existed mainly so lawyers could say, “Yes, we have it.”

A small checkbox.

Pre-ticked, vague, bundled, ignored.

The DPDP Act, 2023 quietly puts an end to that era.

Under India’s new data protection law, consent is no longer a technicality. It is a legal promise and a user right. And most existing privacy notices and consent designs fail that standard.

Why “Check-Box Consent” Is Officially Dead

The DPDP Act does not use the language of tricks or shortcuts. It is explicit about what valid consent looks like.

Consent must be:

Free

Specific

Informed

Unambiguous

Revocable

This single list invalidates years of common industry practice.

A checkbox that users don’t understand.

Consent bundled with unrelated purposes.

A privacy policy written like a courtroom argument.

None of these survive scrutiny anymore.

The law expects that users know what they are agreeing to, not just that they clicked something.

The Real Problem Isn’t the Checkbox. It’s the Intent.

It’s easy to blame design patterns.

But the deeper issue is intent.

Most privacy notices were never written to inform users. They were written to protect companies. Long paragraphs, circular language, broad permissions, and vague promises were features, not bugs.

The DPDP Act flips the objective.

The goal is no longer legal cover.

The goal is genuine understanding.

If a reasonable user cannot explain what happens to their data after reading your notice, the consent is weak, regardless of how many boxes they ticked.

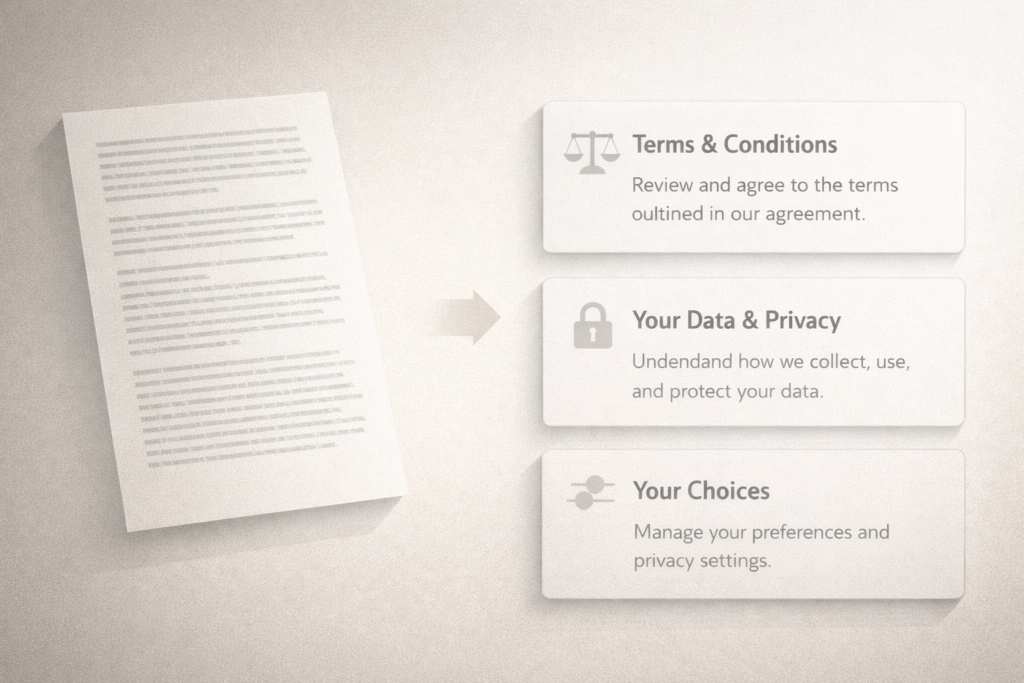

What the DPDP Act Actually Expects From a Privacy Notice

A compliant privacy notice is not a document. It’s a communication.

At a minimum, it should clearly answer five questions:

What data are you collecting?

Not “information you provide”. Be specific.Why are you collecting it?

Each purpose must stand on its own. “Service improvement” is not a purpose. It’s a placeholder.Who will access or process the data?

Including third-party processors where relevant.How long will the data be kept?

Not “as long as necessary”. Necessary for what?What rights does the user have, and how can they exercise them?

Withdrawal of consent should be as easy as giving it.

If these answers are buried or diluted, the notice fails its core job.

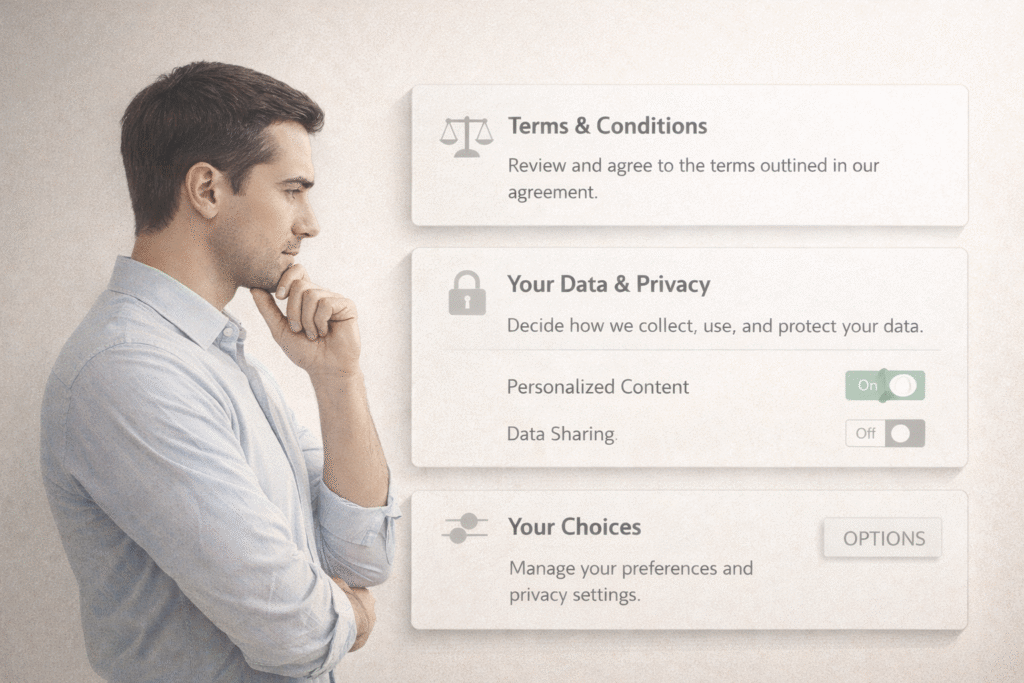

Consent Is No Longer a One-Time Event

Another major shift under the DPDP Act is that consent is not permanent.

Users have the right to:

Withdraw consent

Request correction

Ask for erasure

Raise grievances

And these rights must be practically usable, not theoretically available.

If withdrawing consent requires sending emails, waiting weeks, or navigating dark UI patterns, the design itself becomes non-compliant.

Good consent design assumes users will change their mind. And it respects that.

Designing Privacy Notices Like a UX Problem

One of the biggest mistakes companies make is treating privacy as a legal artifact instead of a user experience.

A well-designed DPDP-compliant notice:

Uses headings and spacing

Avoids dense paragraphs

Separates purposes clearly

Uses simple, conversational language

Provides layered information instead of dumping everything at once

Think of it this way:

If your onboarding flow is clean and intuitive, but your privacy notice reads like a 30-page contract, the mismatch is obvious.

The DPDP Act does not demand complexity. It demands clarity.

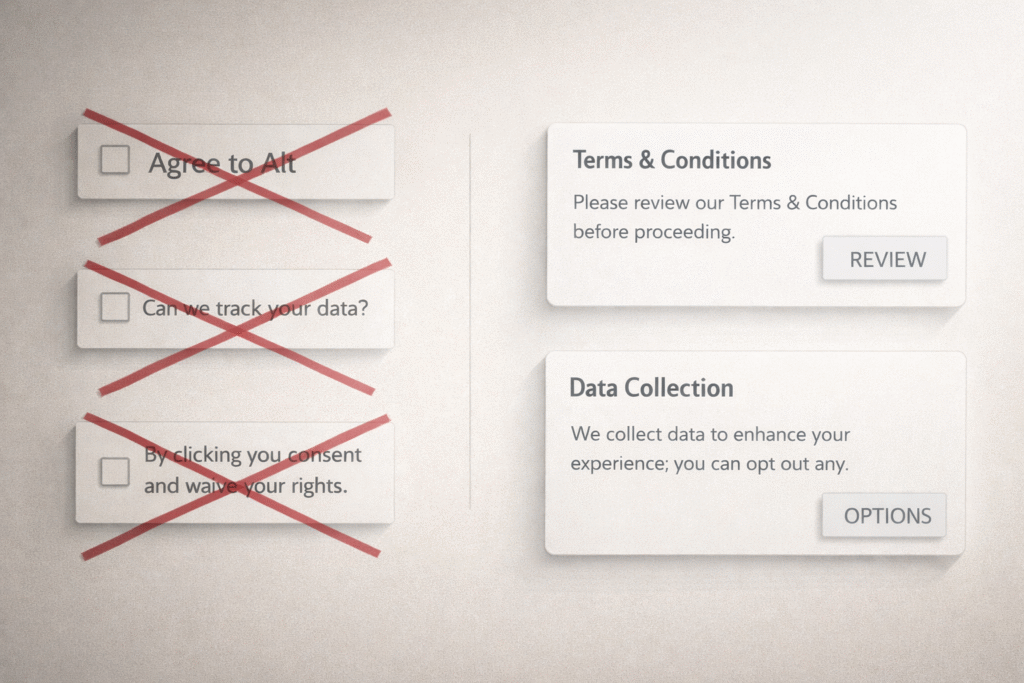

What Definitely Doesn’t Work Anymore

Let’s be blunt. These patterns are now dangerous:

Pre-checked consent boxes

“By continuing, you agree…” banners

One checkbox for ten different purposes

Privacy notices copied from competitors

Consent hidden inside Terms & Conditions

Even if these patterns are still common, that does not make them compliant.

Regulators don’t measure compliance by popularity. They measure it by intent and effect.

Why This Matters More Than Companies Realize

Consent failures are not minor issues under the DPDP Act. They can trigger serious penalties, especially when combined with data misuse or breaches.

But beyond penalties, there is a reputational cost.

When users feel tricked, trust erodes quickly. And in a digital economy built on data, trust is fragile and expensive to rebuild.

Clear consent is not just a compliance requirement. It’s a signal of maturity.

The Shift Companies Need to Make</h2

The DPDP Act is asking companies to make a philosophical change.

From:

“How do we legally cover ourselves?”

To:

“How do we honestly explain our data practices?”

That shift affects:

Product teams

Designers

Marketers

Legal teams

Founders

Privacy can no longer live in isolation. It must be integrated into product thinking.

Final Thought

The death of check-box consent is not a loss. It’s a correction.

For years, consent was treated as noise. The DPDP Act restores its meaning.

Companies that embrace this shift will not just comply. They will stand out.

Those that cling to old patterns will discover, often too late, that clicking “I Agree” no longer means what it used to.